Posted by Nodus Labs | May 8, 2015

Using Efficient Search Methods for Content Structuring

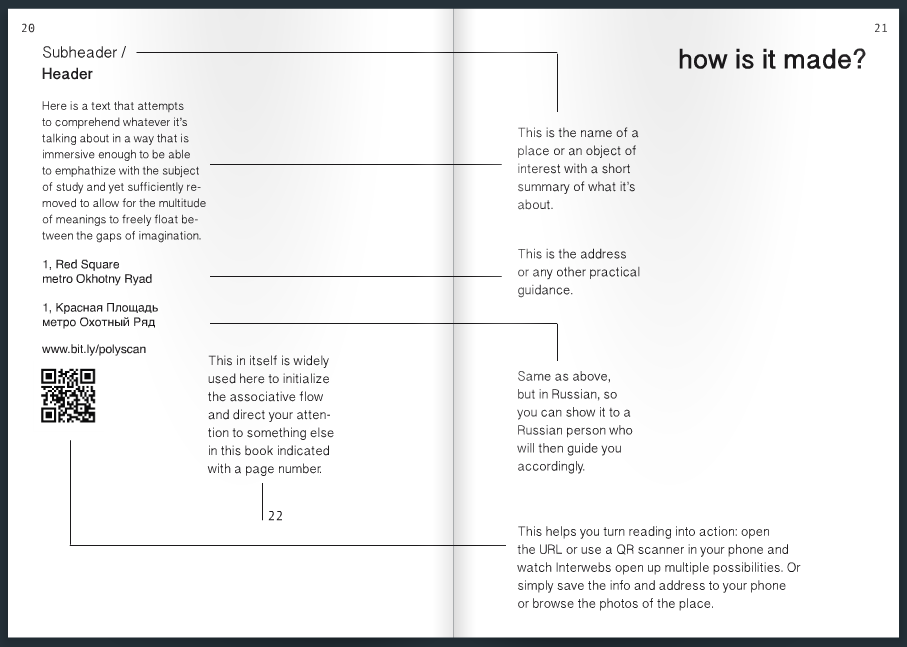

This talk was prepared for a book presentation at Motto Art Bookstore in Berlin. The book, Way to Russia Guidance, is a travel guide to Russia made by Nodus Labs in collaboration with the most popular online resource about Russia waytorussia.net, which utilizes polysingularity as methodology for structuring book’s content.

The Problem of Search and Content Retrieval

Consider you’re looking for something in a book. What are the different strategies you could use?

One option would be to read it from the beginning until the end, but that would take a lot of time and it is not the most efficient method. Using a computer would help, but it essentially does the same and it only works because it can perform millions of operations per second. Asking somebody who knows is another option, but they might not be available or they might not remember.

Another, more complicated task, is to get a quick overview of the book’s content.

It’s comparable to the first task except that you don’t know what you’re looking for.

In fact, this is a very serious problem, especially at the times of informational overload.

So how could it be resolved in the most efficient way?

Inspiration #1: DNA Search Strategies

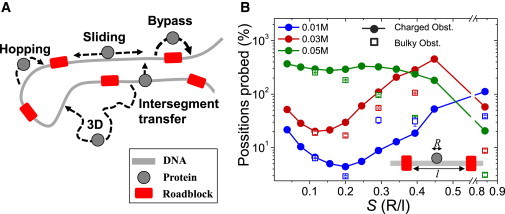

Every cell of our body is actually faced with the same problem. Any process that involves reading genetic information has to first read that information from the long DNA molecule. The binding proteins could just be sliding along the full length of the DNA, but it would take a long time and would not be efficient (they might also encounter obstacles).

The way evolution resolved this problem is a 1D / 3D search (Marcovitz & Levy 2013).

In order to find the right place to bind along the DNA molecule, a protein is sliding across its length for a period of time (this is called 1D search). Then, either at some intervals or because it encountered an obstacle, it performs a “jump” from one place of the molecule to another (this is called 3D search).

The combination of sliding and jumps produces a very efficient search strategy where the protein quickly binds to the parts of the molecule that it’s searching for.

Inspiration #2: Divinatory Narratives

Another example comes from an area, which is different, but is still related to the study of life.

Divinational narratives, such as Tarot and I Ching, have long been used to provide guidance and help find the right information to act upon.

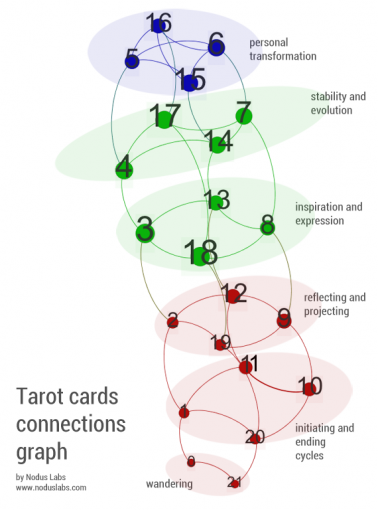

Both Tarot and I Ching are structured in a modular way. There are 22 cards (major arcana) in Tarot, each of which represents a concept and tells a story (read our study on Tarot network structure for more information). I Ching has 64 hexagrams, each hexagram also represents a certain concept or a story.

Divinational reading proceeds through a series of randomized iterations where the reader is choosing one or several starting points to read from. The cards (or hexagrams) then lead to the other cards (or hexagrams), so in the end the reader gets a very good overview of the whole content without having to read through the whole book.

In this way both Tarot and I Ching are very efficient narrative structures in the sense that they allow the reader to get the gist of the content at only a fraction of the time it would take to look through all of it.

The connections between the elements are not random. In fact, there’s a very precise structure at play, which allows the reader to get the fullest representation of the different parts of the narrative.

For example, every card in Tarot is connected to the card before it and after (simply by way of chronological order). It’s like opening a random page in a book and reading a little bit before and after to get the context right.

Then, there are two cycles in major arcana of Tarot, one cycle proceeds from card #1 to #10, the other cycle proceeds from the card #11 to #20. Every card in the first cycle connects to the card in the parallel “parallel” cycle. This parallel cycle is simply a parallel story line that starts in the middle of the Tarot “book” and goes through a similar development as the first story line, but with some alternations. A story that is more mature, in a sense. For instance, a card #2 is connected to the card #12, #5 to #15 and so on.

Finally, the last link is from the beginning of the first cycle to the end of the alternative cycle. It’s like opening a 22-page book on page 3 and also reading the page 19, so you can get an idea about the beginning and the end of the story.

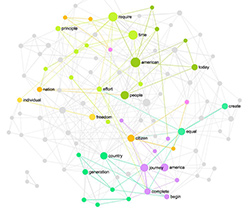

If all those connections that exist between the different cards are represented as a network, we will get a structure that looks like this:

Interestingly, it’s shaped like a helix – a structure that is often found in biology.

As we can see, this sort of network structure is an efficient mechanism for structuring narrative in the sense that if you start “reading” that structure from any point in the graph, you will cover the whole shape with only a few moves along the vertices.

In this way, the structure of Tarot narrative achieves the same goal as the 1D/3D DNA search: it combines the movements along the line (chronology) with 3D jumps across the structure in order to get the whole overview in a more efficient way.

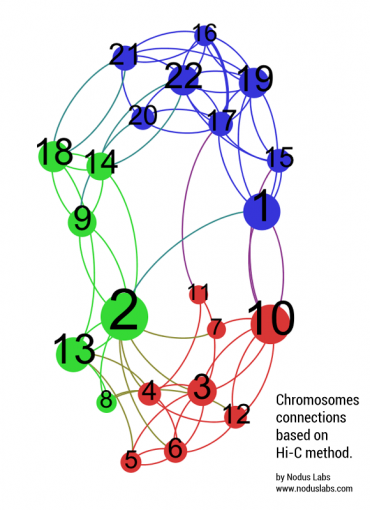

Even more interestingly, this sort of helix structure is related to the way human chromosomes are connected to one another. If we represent 22 chromosomes as a graph (we omit the 23rd one as it’s an X/Y male/female switch) their interactions look very similar to the helix of Tarot, which is another visual evidence that this sort of structure may be very efficient for information retrieval. (See the work of Lieberman-Aiden for scientific background behind this approach)

From Theory to Practice: Building the Narrative of a Book

We decided to apply the both methodologies above for a practical task of structuring the content of a book.

The subject matter selected was the travel guide because it already implies some sort of efficiency in the structuring and also because people usually read travel guide in a rhizomatic way.

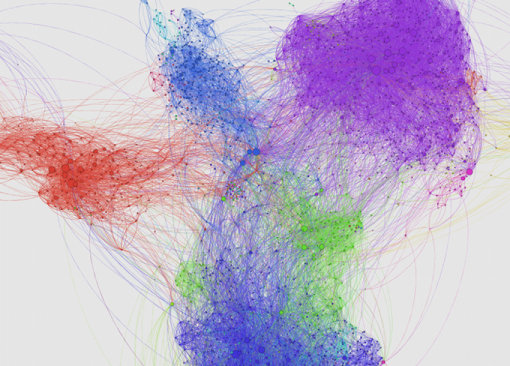

For the sake of simplicity we refer to the methods above (1D/3D search and helix-like narrative structure) as Polysingularity. The reason is that the both methods combine local movements within a certain cluster (page) with long-haul jumps across the clusters (from one page to another). So if we were to represent the content of a book as a network, where the various subjects are the nodes and their connections are the relations between them, we’d get a structure that looks like a combination of singularities that are distinct enough but that are connected to one another.

Following this methodology for the structuring of the book, we identified several topics and the relations between them.

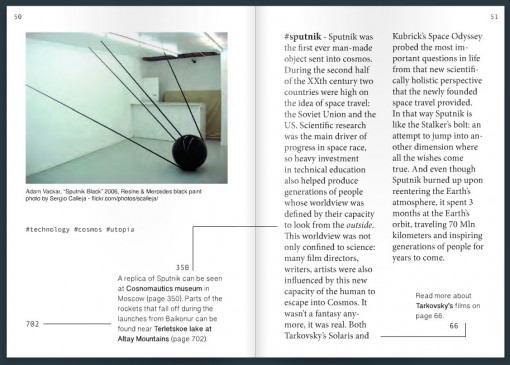

For example, as the travel guide is to Russia, one page is about Sputnik (the famous Russian satellite) and the next page about Kalashnikov gun (another type of well-known Russian military technology). However, the page on Sputnik also links to the museum of Cosmonautics in Moscow but also to a beautiful lake in Altay mountains where the parts of the rockets from Baikonur space launch station fall down to produce amazing lighting effects and to contaminate the nature around.

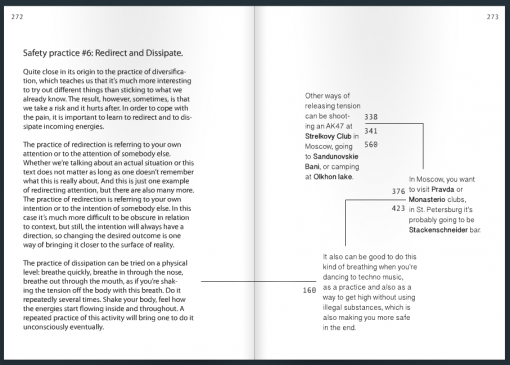

A page with a safety advice for travelers advises them to dissipate any tension that may arise during their trip to Russia by way of dissipation, which can be achieved using physical practices (such as Systema), but also, if they go out to dance to techno music or to shoot at the shooting range in Moscow. Therefore, the original narrative branches out into many different directions and enables the reader to get the full range of contrasting experience.

This sort of structure is similar to the hyperlink structure of internet documents, except that it consciously attempts to focus not only on content that is similar and related, but also on the content that may be at the completely opposite side of the spectre, thus enriching the travelers’ experience and also providing a sort of meta-guiding narrative through the guide itself.

References

Marcovitz & Levy (2013). Obstacles May Facilitate and Direct DNA Search by Proteins. Biophysics Journal

Lieberman-Aiden et al (2010). Comprehensive mapping of long range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science Magazine.